Rhetorical and Literary Devices: Examples and Exercises

Victoria | Equipo de redacción

September 12, 2025

Language isn’t just for sharing ideas in a plain or direct way—it’s also an artistic tool that can spark emotions like joy, nostalgia, anger, trust, or tenderness. To achieve that effect, writers, poets, and even musicians rely on rhetorical and literary devices, because they let them play with words to create super-creative texts that grab our attention and leave us thinking about their meaning.

Even if at first glance it seems like these devices live only in old books or in poems you rarely read, they’re more common than you think: you’ll find them in everyday sayings, in your favorite songs, and in ads on the street or on social media. In this post we’ll walk you through what they are, the subtle differences between them, the main types, and plenty of examples so you can spot them right away.

What Are Rhetorical or Literary Devices?

Rhetorical or literary devices are language resources that tweak the normal use of words to beautify, emphasize, or add extra expressiveness to a message. Think of them as decorative touches that make any statement more attractive and that create emotions or vivid mental images.

One key point: rhetorical devices don’t literally change the meaning of the words—they transform how we perceive them to create greater impact.

Examples:

“Her words touched my heart.” (metaphor)

“He runs like the wind.” (simile or comparison)

Rhetorical vs. Literary Devices: Is There a Difference?

We often treat these terms as synonyms, and they can overlap, but there’s a small distinction:

Literary devices: Rhetorical devices used specifically in artistic texts such as poetry, fiction, or theater.

Rhetorical devices: Any stylistic resources that enhance language; they can appear in everyday speech, advertising, speeches, and more.

In short: all literary devices are rhetorical, but not all rhetorical devices are literary.

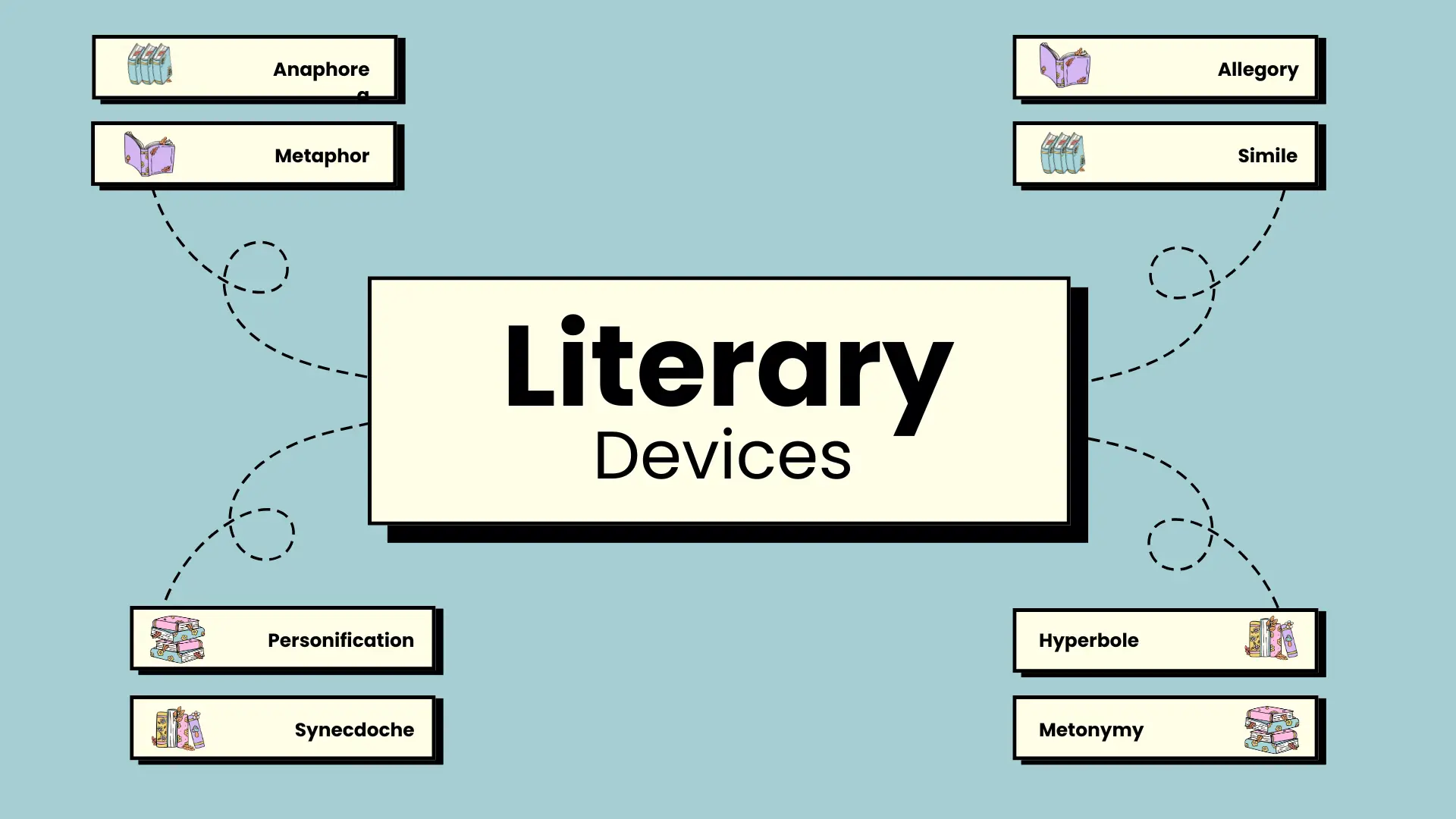

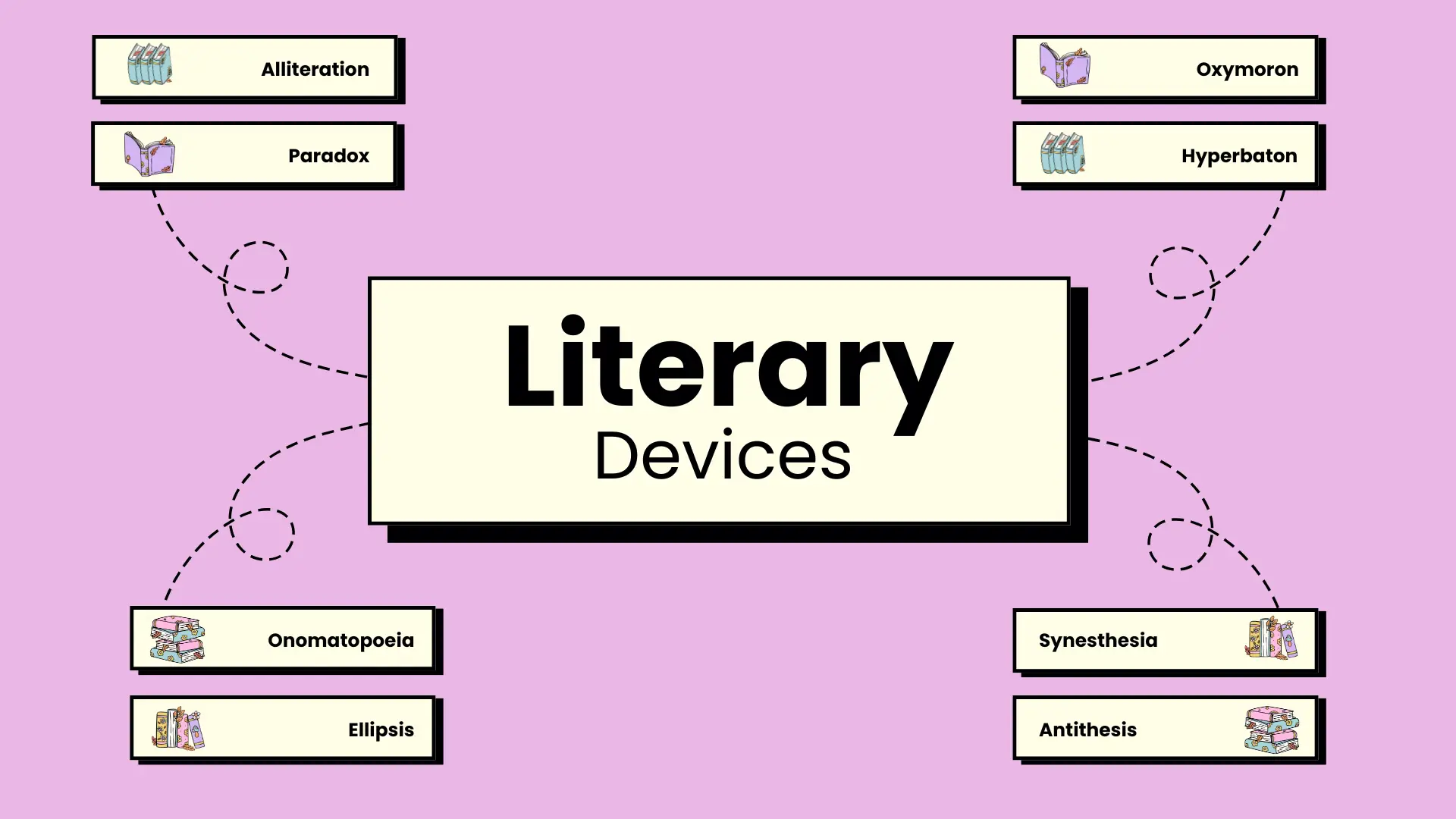

Types of Rhetorical (or Literary) Devices

Because there are so many, they’re usually grouped into three main categories:

1. Sound or Diction Devices

They play with the sound and form of words.

Alliteration: “My mom makes marvelous muffins.”

Onomatopoeia: “The clock went tick-tock.”

2. Thought Devices

They highlight ideas or feelings by shifting meaning.

Hyperbole: “I’m so hungry I could eat an elephant.”

Personification: “The wind sang through the window.”

3. Structural or Syntactic Devices

They alter word order or sentence structure.

Anaphora: “Early rose the dawn, early came the day.”

Hyperbaton: “From the hall in the shadowy corner…”

Key Literary Devices and Examples

Metaphor

Identifies one thing with another based on similarity, without using “like” or “as.”

Examples:

“Raúl is a caveman when it comes to social media.”

“This place is a paradise.”

“Your room is a garbage dump.”

Simile or Comparison

Links two elements using connectors such as like, as, similar to.

Examples:

“Her hair was red like fire.”

“He was so angry he looked like a lion.”

“He sleeps like a baby.”

Hyperbole

Extreme exaggeration for emphasis.

Examples:

“I told you a million times.”

“You’re the most beautiful thing in the universe.”

“That movie felt endless.”

Personification (Prosopopoeia)

Gives human qualities to objects, animals, or natural phenomena.

Examples:

“The walls have ears.”

“The wind sang all day long.”

“Winter knocked at his door.”

Anaphora

Repeats one or more words at the beginning of consecutive lines or sentences for rhythm.

Examples:

“Here everything is known, here nothing is forgotten.”

“Alive they were taken, alive we want them back.”

“You know her, you will know.”

Antithesis

Sets opposite ideas side by side to highlight contrast.

Examples:

“Love is so short, forgetting is so long.”

“The richer he became, the poorer he felt.”

“The ice burned his hands.”

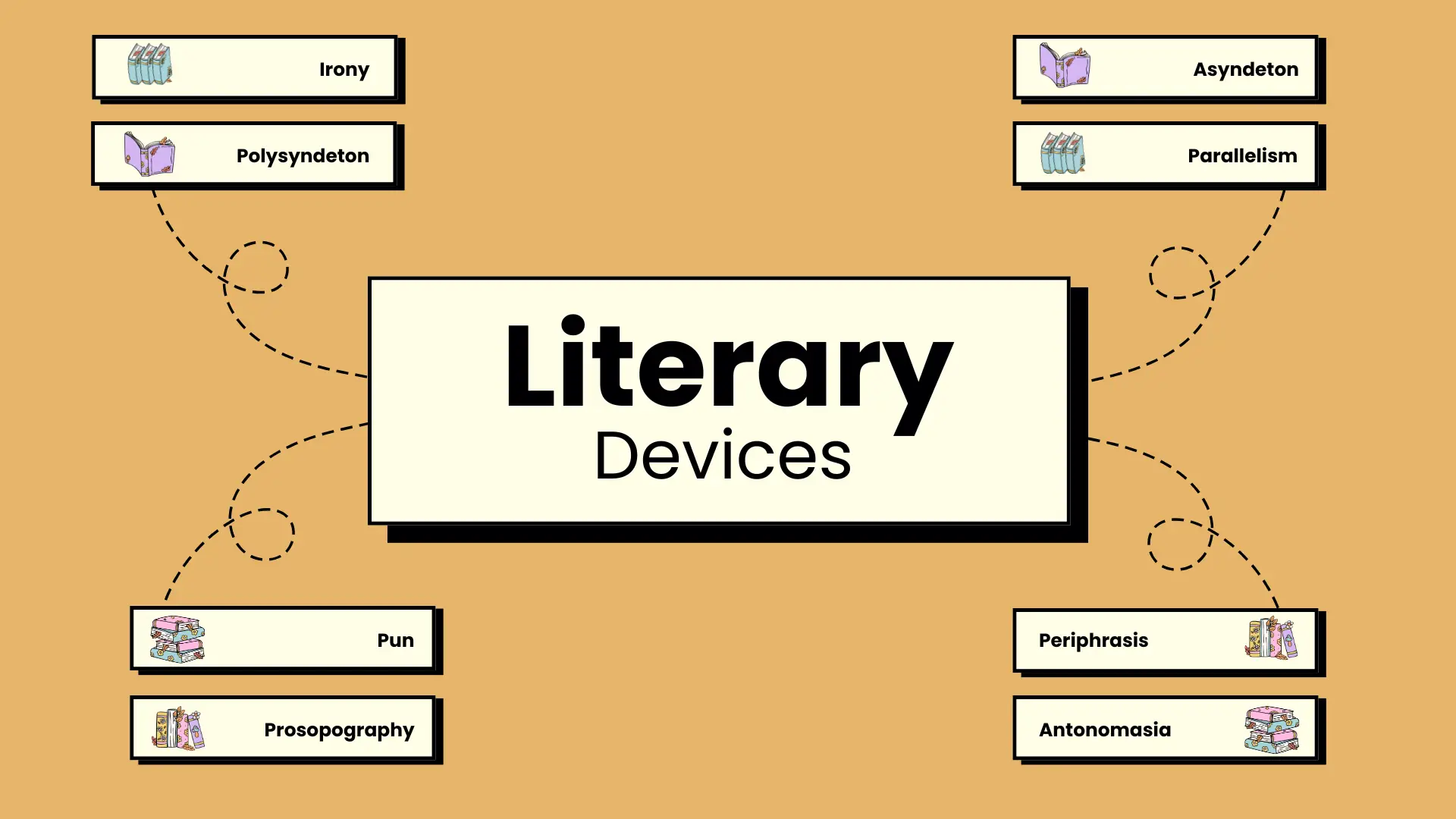

Irony

Says the opposite of what is really meant, often humorously or critically.

Examples:

“Wow, right on time!” (when someone is late)

“But the Titanic was supposed to be unsinkable, wasn’t it?”

Oxymoron

Joins two contradictory words in one expression.

Examples:

“A deafening silence.”

“A friendly fight.”

“A small crowd.”

Ellipsis

Leaves out words that are understood from context.

Examples:

“It itched a lot, didn’t it?” (…didn’t it itch for you?)

“We went upstairs for the cat but [it] wasn’t there.”

“I want green sauce; he, red.” (he wants red)

Polysyndeton

Uses more conjunctions than necessary.

Examples:

“He laughs and cries and dreams and sings.”

“My laptop is blue and big and pretty.”

“Night came and despair and cold."

Asyndeton

The opposite of polysyndeton: omits conjunctions to create speed or urgency.

Examples:

“He counted the seconds, minutes, hours, days—yet never arrived.”

“Meat, lettuce, tomato, avocado.”

“Veni, vidi, vici.”

Paradox

A seemingly contradictory statement that reveals a truth.

Examples:

“Thank God I’m an atheist.”

“It was the saddest smile I’ve ever seen.”

“To arrive quickly, there’s nothing better than going slowly.”

Prosopography

Describes someone’s physical appearance.

Examples:

“Tall, green-eyed, and curly-haired.”

“Her eyes were dull, her skin pale.”

And there are many more—pleonasm, synonymy, synecdoche, chiasmus, periphrasis, etopeya, pun, sarcasm, and so on.

Rhetorical and literary devices prove that language doesn’t just inform—it also moves, persuades, and transforms. Learning them not only helps you understand literature better but also lets you express yourself more creatively every day.

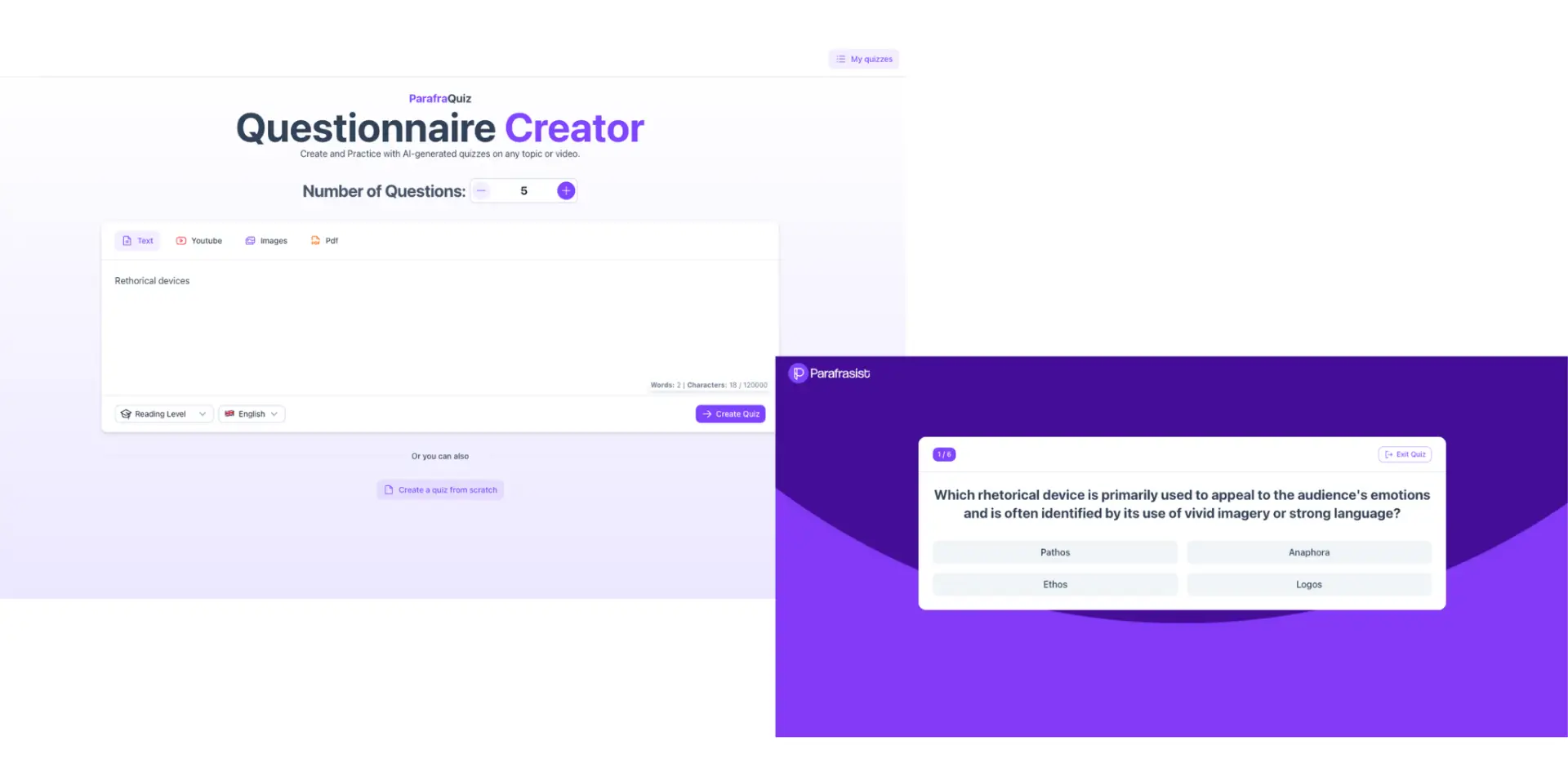

If memorizing each definition feels tricky, you can always practice online with ParafraQuiz: just enter the topic and start answering questions or spotting literary devices in sample sentences.

Next time you read a poem, listen to a song, or glance at an ad, pay attention—you’re bound to find a hidden metaphor, a disguised hyperbole, or an unexpected paradox.